The golden rule: Performance measures are based on objectives. A performance measure should not exist unless it is based on an objective. Without wanting to deflect attention away from performance measures, a small digression is required; what do we mean by ‘objective’? Let’s not get carried away with distinctions between strategic objectives, objectives and goals at this point, let us just simply agree that an objective is anything that contributes to an organisations strategy and vision. So the first question to ask is:

1. Is the performance measure linked to a valid company or organisation objective?

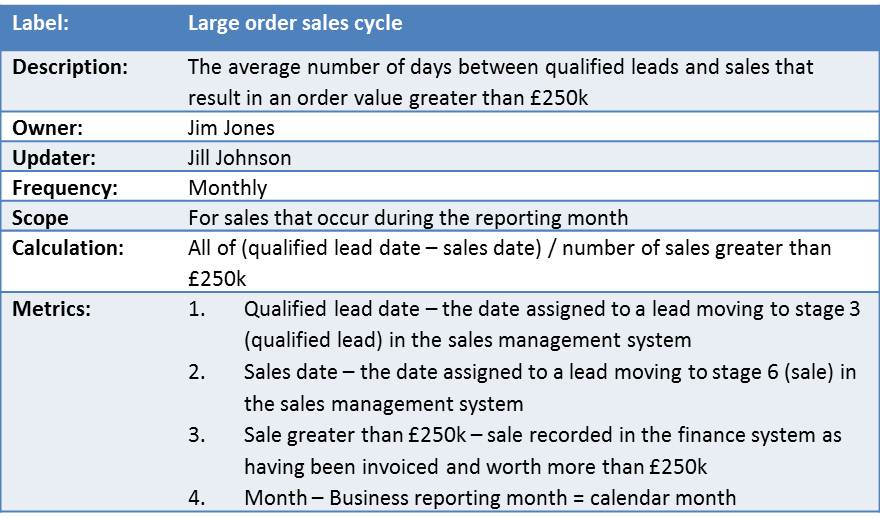

If it is not, then think very hard about why it is there in the first place. Next we need to look at the difference between a ‘description’ and a ‘label’. These are not interchangeable. We all too frequently use simple labels to describe our performance measures. A very common example is ‘Sales Order Cycle Time’. In general we would all agree that this means the time between a receiving a sales lead to the time a piece of business is closed. This of course, does not take into account many of the variables associated with this performance measure. By way of example the following two performance measures could be used to describe ‘Sales Order Cycle Time’: 1. “the average number of days between a qualified lead and a sale” or 2. “the percentage of sales generated within 30 days of lead qualification”. As can be seen, the measures are quite different. If you add a typical ‘lead’ measure into the mix, for example: “The number of sales people trained in selling our product portfolio to grade III certification”. We can see that the measure is entirely different. However, all three are valid performance measures that could be given the label ‘Sales Order Cycle Time’. The point here is that both a description and a label are required. The first to ease the task of reporting, that is, a short unique label to identify the performance measure in a generated report and the second to give real clarity to what we are actually trying to measure. The second question is:

2. Does the performance measure have a clear description (and unique label)?

There are a couple of things we should be thinking about to ensure the description is clear: Is the description in the form of a sentence? Does the description include ‘tangible’ words, the things that can be counted? Is the ‘type’ of measure included in the description e.g. average or percentage?

When selecting performance measures for a scorecard it is inevitable that too many measures will be identified. We have a tendency to want to measure everything and everything is important. However, best practice dictates that there should be a few good measures rather than a lot of average measures. Therefore there is a need to rate your set of performance measures and then use the ones that are both meaningful to the business and feasible to measure while putting a high level of common-sense into the decision making process. The third question is:

3. Is the measure meaningful and can I actually measure it?

If you want to get anything done, then it is essential that ownership is assigned. If an individual has been given responsibility to deliver and is accountable for success, then you are much more likely to succeed. This is as true of projects as it is of performance measures. If we assume (as we have above) that performance measures are always associated to objectives then the objective is the thing that needs to be done and the performance measure is the proof of success (or otherwise). They are integral to each other and need to have an owner to drive, monitor and manage progress. The fourth question is:

4. Has ownership been assigned to every performance measure?

A performance measure is meaningless unless it can be compared to something. The actual value of the measure has to be compared to what would be considered good, bad or indifferent. In performance management terms we often refer to a RAG status that is Red, Amber and Green. This is where ‘threshold’ values have been assigned to the measure to give an instant visual clue as to where we are in comparison to a target we have set. The comparator could be a target based on previous performance or on a notional future performance or even a made-up value. Whatever the target, it needs to be considered as reasonable and achievable. A RAG method is by far the most common and would mean a threshold has to be set to indicate when the performance measure should turn Red and another set to indicate when it should turn Green. In other models there may be four colours, the fourth e.g. Blue, might indicate an over-achievement (often useful in sales). You may even need to consider a Red, Green, Red variant where a number above or below a threshold would be considered bad. The fifth question is:

5. What are the thresholds associated with the performance measure?

This may seem like a lot of effort to go to when defining performance measures, however, once the process has been gone through a couple of times it is relatively straight-forward and pays huge dividends in the long term. Typically a form like the one below can be used to capture this information, in this example we have used a more specific version of the example given above:

For more information on this topic and other corporate management tools, be sure to visit the Intrafocus website